Why ‘community’ becomes a liability at scale

And how some teams turn it into an advantage

Community feels like leverage because it appears to build on its own momentum. Early users show up, talk to each other, and give feedback without much prompting. It feels lighter than sales and more genuine than marketing.

At that stage, early users act as signal rather than noise. You can hear what’s landing and what isn’t because the group is small and engaged. Patterns show up quickly, and they’re usually directionally right.

This is why it works at small scale:

Conversations stay personal

Feedback loops stay tight

Expectations stay implicit

Founders can stay close without adding process

That balance holds early on. The problem is that it rarely stays that simple for long.

When community quietly turns into governance

At first, feedback is casual. People share thoughts, react to ideas, and suggest improvements. Over time, that informality can start to feel like authority, even if no one ever agreed to it.

The shift is subtle. What began as a contribution slowly turns into an expectation. Some members start to feel invested not just emotionally, but directionally. Decisions stop feeling advisory and start feeling owed.

That’s when things slow down. Every choice carries more weight. Explaining decisions takes longer. Momentum drops, not because the founder is unsure, but because too many voices now feel like they need to be accounted for.

Image: Community creates signal, but direction still needs to converge.

The false choice founders think they face

Founders often feel boxed into a bad choice. Either you listen to everyone, or you shut down and stop engaging altogether. Both feel risky in different ways.

Going silent rarely reduces drag. It usually does the opposite. When expectations aren’t reset, people fill in the gaps themselves, and assumptions spread faster than clarity ever did.

That’s where trust starts to erode. Not because decisions were wrong, but because participation was never clearly defined. When people don’t know how their input is used, or when it stops mattering without explanation, uncertainty does more damage than a firm boundary ever would.

Governance vs velocity isn’t the real tradeoff

Founders often frame this as a speed problem. More voices mean slower decisions. Less governance means moving faster. But that’s not actually what breaks things.

The real problem is undefined influence. When it’s unclear who gets input, who gets a vote, and who gets visibility, every decision starts carrying hidden expectations.

That’s where speed and legitimacy get tangled. Decisions slow down not because founders hesitate, but because they’re trying to avoid surprising people who feel involved. Over time, momentum drops as decisions shift from direction to alignment.

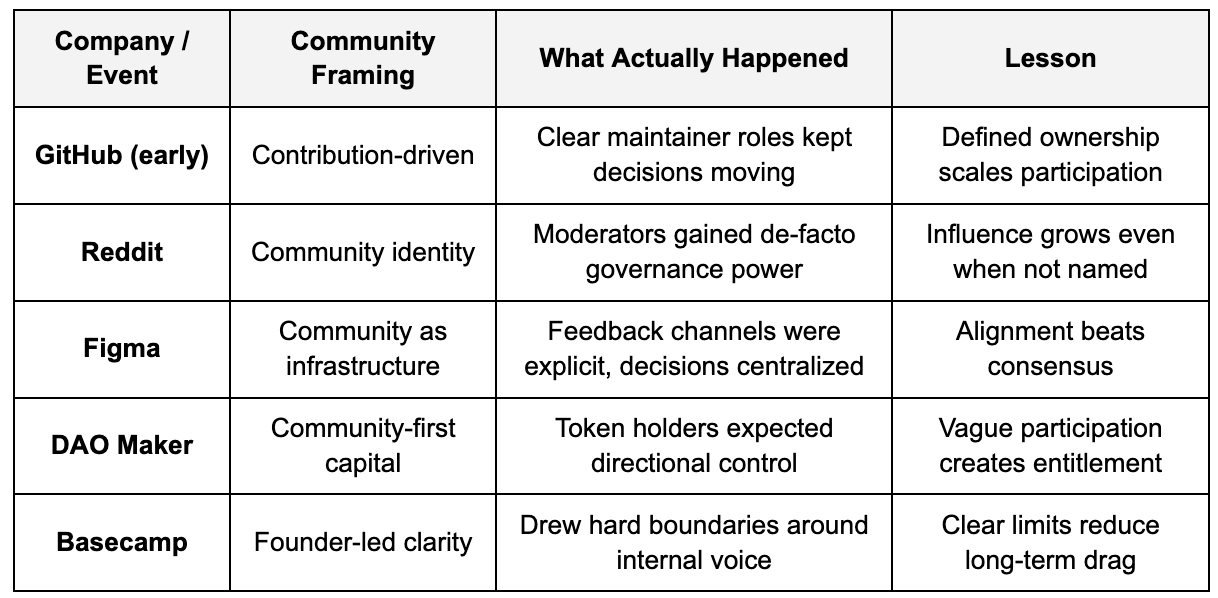

Clarity fixes this better than consensus ever does. When participation is clearly defined, decisions can move quickly and still feel fair, even at scale. In the end, clarity beats consensus. You can see this dynamic play out clearly in real companies.

Intentional community as a designed system

The shift that matters most is treating community as something you design, not something that happens. When it’s built with intent, the community supports momentum instead of quietly slowing it down.

That starts with purpose, not vibe. People should know why the community exists and what role it plays in the company. Without that, participation drifts and expectations blur.

An intentional community usually has a few clear traits:

Inclusion is explicit. People know why they’re there and what they’re there to do.

Feedback has a home. Input is welcome, but it flows through defined channels.

Decisions live elsewhere. Final calls sit with clearly named owners, not the crowd.

Separating feedback spaces from decision spaces keeps both healthy. People can contribute without assuming control, and founders can move forward without constantly renegotiating legitimacy.

Practical design patterns founders can use

The patterns below don’t require heavy process or formal governance. They rely on simple design choices that prevent most of the drag from appearing.

Bounded forums: Each space exists for a specific purpose, and that purpose is stated up front. People know what kind of input belongs there and what doesn’t.

Channel direction: One-way channels are for updates, decisions, and context. Two-way channels are for feedback, questions, and discussion. Mixing the two is where confusion creeps in.

Time-boxed input: You can open a feedback window, close it, and then decide. This keeps discussions productive without turning them into ongoing negotiations.

These patterns don’t shut people out. They give participation shape, which is what keeps things moving as scale increases.

What founders must say out loud (but often avoid)

Most community problems don’t come from bad intent. They come from things that were never said clearly in the first place. Founders assume boundaries are obvious. But they rarely are.

Saying these things out loud feels uncomfortable, especially early on. It can feel like you’re limiting people or taking something away from them. In reality, you’re doing the opposite. You’re giving participation a shape people can actually understand.

What the community does not control: Not every discussion is a decision. Not every opinion carries equal weight. Final calls sit with clearly named owners, even when feedback is welcomed.

What participation actually means: Sharing input, surfacing problems, and offering perspective. It does not mean steering direction or expecting outcomes to change.

Why transparency is not the same as democracy: Transparency explains decisions and makes reasoning visible. It doesn’t require voting on every choice or outsourcing direction to the group.

When founders avoid saying this, communities fill in the gaps themselves. When founders say it early, trust tends to rise, not fall. Clarity removes friction that no amount of goodwill can fix later.

The long-term advantage of doing this early

The biggest payoff shows up later. When boundaries and participation are defined early, they tend to hold as the company grows instead of needing to be constantly renegotiated.

Clear expectations reduce social debt over time. Founders don’t have to unwind assumptions or correct course as new people join. Fewer conversations need to be revisited, and fewer decisions need to be relitigated.

Decision-making also gets faster and more durable. When ownership is clear, choices are easier to make and easier to stick with. There’s less backtracking, fewer reversals, and less energy spent re-explaining why something changed.

Over time, the community grows rather than fragments. People know how to contribute without competing for control. The result is a community that strengthens the company rather than quietly pulling it apart.

Community as infrastructure, not identity

Calling something “community-first” sounds good, but it’s too vague to scale. It describes intent, not structure. Without design, it turns into a label that means different things to different people.

Treating community as infrastructure changes the frame. Infrastructure exists to support the system, not define it. When designed well, it creates alignment without requiring constant approval or consensus.

The founders who get this right don’t chase agreement. They design participation so input improves decisions without slowing them down.